Return to flip book view

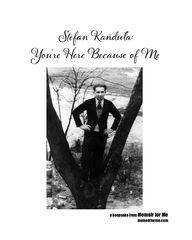

Stefa Kańduła:Yo’r Her Becaus of Ma keepsake from Memoir for Mememoirforme.com

Over the course of two Saturdays in the winter of 2018, at his granddaughter Anna’s request, Stefan Kańduła was interviewed about his life in an eort to preserve the narrative of our family’s origins and immigration to the United States. While his remaining children focused on clearing, organizing his home in the Portage Park community of Chicago to prepare for it for sale, Stefan relaxed in his chair at the kitchen table and recalled the details of his life to be recorded for posterity. As the Kańduła patriarch, he is the eldest member of a family of Polish immigrants displaced by World War II. In his ninetieth year of life, he still has a gentle spirit and a mirthful twinkle in his pale blue eyes. Pressed to share what he believes to be his greatest achievements have been in life, he quickly deects to the descendants’ accomplishments. He beams with pride when he talks about his family, as he should, since we owe our existence to him. Humble and compassionate, he is often described by his children as their salvation in an otherwise tumultuous childhood home. His long life is marked by a keen sense of resourcefulness; seeking satisfaction in life’s simple pleasures.Stefan with granddaughter Anna, 20043

Stefan’s birth certicate states that he was born in a village referred to as “Podlesie,” Powiat Nowotomyski on July 21, 1928. (Podlesies refer to historical townships in the eastern part of Poland. The term may also translate to, “under Polish rule” during the medieval period, or even communities located in geographically forested areas, which is the reference most familiar to him.) This small cluster of only a few homes was located approximately 55 kilometers (or 34 miles) northwest of the city of Poznań located in northwest Poland. Before his third birthday, his parents moved their growing family to the small farming community of Pawluwek. This is where he grew up. It wasn’t really a town—just three houses in the whole village. We describe it in Polish as “podlesie,” or “under forests.”Stefan’s parents were Franciszek (Frank) and Apolonia (née Pawełczak). His paternal grandparents were Walenty and Antonina (née Wolny) Kańduła, but Stefan never met them because his father was left to fend for himself when he was only a child.My father was orphaned at nine years old. He worked for neighbors, doing odd jobs for food and shelter. I look like my dad. Even my disposition is like my dad. He didn’t get mad so fast. His mother, however, was a dierent story.My father was the disciplinarian, but mother was erce. Tiny, but erce – she was not even ve feet tall. 4Apolonia and Frank, 1943 Stefan’s grandmother, Anna Orwat Pawetezak

Apolonia may have been modeling behavior learned from her own parents, Anna (Orwat) and Marcin Pawełczak. Both his mother and maternal grandmother shared a similar temperament to another woman Stefan would meet later in life who would play a signicant role in his life.Babcia was a tough woman. She would hit us with a rope or belt when we were bad, but not too badly or often.By this time, Stefan had two younger siblings: Frank (b. 1930) and Mary (b. 1931). While each new birth was a welcome addition, the family, now numbering ve, struggled in Poland as resources, already stretched thinly, were tested even further.Basic necessities were either hard to get or you couldn’t aord them. Our clothes consisted of patches upon patches—there were more patches than pants. Clothes were passed down until they fell apart. Our shoes were cobbled together with old leather and wooden bottoms.Powiat Nowotomyski, Poland

Food scarcity was the biggest concern of his family, a fear not lost on young Stefan. If you didn’t work in the eld, you starved. There was no money to buy it. People were dependent on their own hands—whatever you could put in the ground and grow. Stefan’s family worked as farmers tending someone else’s land in exchange for housing. You got room and board, and your family got to live there. One particular owner, Hrabia Łnski, had a driver with a carriage. He was a big shot. He was pretty fair—people could make a living. That’s all they wanted in those days. Here, the Kańduła family grew potatoes, carrots, cabbages, cucumbers wheat, rye, and barley. They also raised cows, horses, pigs, goats, rabbits, chickens, ducks, and geese. Stefan’s Holy Communion, 1937

We raised lots of rabbits because they grew fast. Three months and they were ready to go into the pot. Beef was for special occasions or if something happened and if you had to kill a cow. In those days, there was no refrigeration, so meat was either eaten right away or cured in salt for later consumption. Stefan still has strong, fond memories of eating fresh baked bread.Oh, what a smell, that was good! We’d also churn our own butter. A life-long lover of food, it’s only natural that many of his fondest childhood memories include the making and storing of produce they grew, especially, lots, and lots of homemade sauerkraut.We stored it in big drums. When you needed some, you went and got it to make sauerkraut soup. Or you had potatoes and sauerkraut. We’d add lard from a pig, fry it, and add it to sauerkraut. It was good!Stefan adds that because there wasn’t much food available, everything they consumed during such dire times was always smaczne or “avorful.”It was good because there was nothing else.Their home had only two rooms and was shared with extended family.There was a big kitchen and big room. You could put six beds in there. My family, my mother’s sister’s family, and my grandparents all lived in the same house. 7Considering the rabbits as a POW on a german farm, 1940s

The house was lit with kerosene lamps and candles and heated by wood-burning stoves. When it was cold outside, it was cold inside. We had a little stove in the sleeping room that you ll with wood before you went to sleep. When the re went out, it was cold as hell. Somebody had to wake up and put the stove back on. The house was a shelter for sleeping and eating and Stefan remembers spending as much of his childhood as possible outside. We were always outside playing, unless it was cold or rainy. We played with a stick and ball made from rags because we couldn’t aord a real one. My village was so small that all the kids knew one another.Unfortunately, playtime was limited because of the demands of work. Everyone had to help out, regardless of age.I did whatever needed to be done. I helped plow. I planted the potatoes, and I harvested them. We used dierent machinery to harvest the crops—mostly wheat and rye, and oats and barley for the horses. Cars were a luxury not seen in rural Poland at the time.Everybody walked. It was three kilometers to church. You’d have to sometimes walk in the snow up to your knees, but you still went to church.Learning to drive a plow, 1940s Learning to work a German farm, 19418

Stefan’s family had two bicycles, which were mainly used by his father and grandfather. If you could aord a bicycle, that was something. My father would teach us how to ride a bike, but if you fell o, you better not dent the bike!School was another place Stefan would walk, but unfortunately, he would only be able to attend for three years. I had to walk three kilometers to school (almost two miles) each day. The school had two rooms—grades 1–2 grade in one room, and grades 3–4 in another. I liked it, but then the war broke out and that was it. In 1939, Germany invaded Poland. Stefan’s father, Frank, was drafted to ght, but was soon captured as a prisoner of war in Germany. 9Kańduła Auslanders in Germany, 1944

My mom did everything she could do to keep the family going. Her mother cared for us kids while she was out working in the elds. Frank was held as a prisoner of war from 1939 to 1941. Due to a labor shortage in Germany, he was released from prison to work on a farm owned by Elvis and Krista Gaisthefel Pelengar. Frank was permitted to invite his family to join him, provided that they, too, helped out on the farm in exchange for room and board. Shortly thereafter, Stefan, his mother, and his two siblings left for the town of Ahlen, in the Westphalia region of northwestern Germany. Stefan remembers life in Germany as initially being an improvement to that of Poland. The German landowner provided Stefan and his family with food, shelter, and clothing. We ate ve times a day: at 7, 9, 12, 3:30 (coee), and 7. We only ate three times a day in Poland. There was a good cook, who fed ve guys working on the farm, plus their families.Here, Stefan and his family lived in a house that was built for the workers, which was equipped with a few modern luxuries. The home was clearly an upgrade from their former residence in Poland. 10With mom and sister, 1945

There was a kitchen and sleeping area. We had electricity, but no refrigerator. There was a washing machine made from wood. Sometimes it took two guys to wash the clothes, but they came out nice and clean. Everything was dried on the line outside.Wistfully, Stefan remembers this time as being lled with more personal freedom. The real dangers of war were lost on the youth.As kids, we didn’t realize what was going on. We were too stupid to get scared (at least at rst). The older people were concerned. At that time during the war, there was nothing you could do for fun. We’d go for a walk, go swimming in the river. It was a dierent time.While his family enjoyed slightly improved living conditions in Germany, many locals viewed Stefan and his family as unwanted outsiders. The term “ausländer” was used to describe any non-German in the country. Literally meaning “foreigner,” it had a derogatory connotation at the time, adding to the stigma they already carried as prisoners-of-war. We had to wear a yellow labor badge with a “P” on it for Poland. Every Ausländer (a negative term for people from other countries) had a dierent badge. Some of the Germans were mean, they didn’t like people from other countries.11With the farmers who hosted them - Stefan is in lower right corner, 1947

But at Stefan tells it, he believes the Germans really didn’t have a choice. Ausländers were necessary to do the work Germany soldiers were not able to do while they were o ghting in the war, but that didn’t prevent resentments. Mercifully, Stefan and his family were spared such degradations on the farm where they worked, provided they adhered to local laws for P.O.W.s. One such rule Stefan readily recalls is the strict curfews they had to keep.Most German men were in the in Army, and someone had to provide food and make bombs in the factories. On the farm, they didn’t use that term for us.World War II is infamous for the Nazi systematic killing of over six million Jewish people in the Holocaust. Word had even gotten around to the rural farms of what was happening all over Germany, Austria and Poland.We knew about the Jewish [concentration] camps. In these camps, Jews were not known by name, just by the numbers on their arms. 12 Stefan as a camp counselor in DP camp, 1947

By 1945, the war began to turn against Germany. Increasingly, British and American bombers began to penetrate German defenses and bomb its factories, ports, railroads, and other targets. We were frightened by the English bombers in the daytime, and the American bombers at night. When there was a moon, you could see the planes. One time, Stefan was caring for horses in a meadow when he noticed a plane overhead. The American plane was ying so low to avoid the German guns. I dropped to the ground. If a pilot were mad, he’d shoot at anything that was moving. At seventeen, Stefan remembers a trip with some friends into the city of Ahlen.There were lots of Polish people in the city. We had to walk there because Ausländers could not have bicycles. While in Ahlen, American bombers suddenly appeared in the sky above them. Stefan (middle of the back row with no shirt) ,1947

We didn’t know what do, so we hid behind a house. The bomb hit the other side of the house. That’s when we got scared! You should have seen how fast we ran. The bombers were trying to hit factories and destroy key German infrastructure. They were dropping phosphorus bombs. They came down and looked like Christmas lights—beautiful. But when they hit the ground, they would burn everything in sight—even the asphalt in the streets. Germany was losing the war, and its leaders surrendered unconditionally to the Allies on May 7, 1945. Stefan recalls the night the war ended. Along with the other resident workers on the farm, he, his mother and siblings sought shelter in a bunker while the bombing thundered outside. In the morning, the family cautiously emerged, now freed prisoners of war. Instead of packing up and leaving immediately, Frank and his family set to work continuing on doing the daily tasks because once you’re committed, you don’t just quit.The cows still needed to be milked. Somebody had to do it.For a while, American, British, and Russian troops occupied the country. We were scared when the Americans arrived. There were tanks and more tanks, and Jeeps with machine guns in front. It was something to see. The American army was full of people of dierent nationalities. 14Stefan (with knees up) with friends in uniform post war, 1946

When the American soldiers arrived, they gave the Polish people three days to do whatever they wanted to the Germans in retaliation. “You can kill them, whatever,” they said. A lot of Germans were killed or beat up. People who had been forced to work in coalmines or factories abused the Germans. After about a week, the American soldiers moved out. The Americans went to the south, and they were replaced by British soldiers, who were stricter. Stefan and other foreigners displaced by the war were aided by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRA), an international relief agency. The displaced persons (or “D.P.s”) lived in military-style barracks as a temporary shelter.It was like the Red Cross. Then, ERO, another organization came in to help people. It helped refugees relocate to Canada, Argentina, Australia, Brazil, all over. Around this time, seventeen-year-old Stefan began driving trucks for the Civil Military Labor Association, a division of the British army. The British were sending soldiers home, and they needed people to take care of things in Germany. They needed somebody to make deliveries, so I drove a truck in a huge convoy of trucks. You had to be careful—we were carrying ammunition.15Posing with friends in the Civilian Military Labor Organization (CMLO), Germany,1947

Stefan became so skillful behind the wheel that he taught others how to drive.It was hard to teach people sometimes. There was one guy shaking and I said, “take it easy.” After that, he was a better driver than I was. We also had to keep the trucks clean; if not, we had to clean them again.Then in 1948, Stefan met a feisty, young woman in Germany who would change the course of his life forever.I met Jadwiga in one of the camps. We started talking, kidding around. We’d go for walks. One thing led to another as it does with young people. It was stupid love. I liked her looks, her gure, everything. We made a promise to marry. The years following the end of the war were chaotic in central Europe. This stress was compounded for “Displaced Persons”, especially when the Germans came back from war wanted their jobs back from Poles and other “Ausländers.” They wanted people to go back to their homelands. They tried to force us back. Trains were loaded to go back to Poland, but the train would really be going to Russia. My father hesitated and did not go. 16In 1946

Someone encouraged Stefan’s father to go to Australia. Since the family decided it was not likely they be able to return to Poland safely, they agreed it would be best to relocate to another continent.Because he was a farmer, my father was promised land after working, so he applied to go to Australia and the United States. The papers to come to America came rst.In August 1949, Frank and Apolonia Kańduła, along with their two youngest children, nally left Germany bound for a new beginning after living as refugees in several dierent Displaced Persons camps for over four years since the war’s end. When they arrived in America, they stayed at the YMCA in New York City. Since Stefan was twenty-one years old by this time, he was considered an independent adult and would need to apply separately for sponsorship in order to leave and join his family in the United States. It took three months, but he nally found a sponsor in North Carolina and in November 1949 boarded a ship for Boston, Massachusetts in the hopes of being reunited with his family.17Stefan with other driving instructors, 1947

It took eleven days to cross the Atlantic Ocean on the ship. It was not a cruise ship, but a big cargo ship, the General S. D. Sturgis. The rst two days of the journey were okay. We had plenty of good food.But when the Sturgis exited local waters and reached the Atlantic, that’s when the trip got rough. The ocean waves took a ferocious toll on Stefan’s enthusiasm. I was sick as a dog. I couldn’t eat. I could only drink water with lemon. You had to belt yourself into this little bed or you’d fall out. Backpacks were ying from one side of the room to another.Late in 1949, Stefan nally arrived in Boston before taking a train to New York City. Here he had an encounter with one of the greatest loves of his life: the pastry.I spent two nights in a hotel. I also had a doughnut for the rst time. It tasted good, oh yeah!Here Stefan learned that not only his family had already moved on to work on a farm in Long Island, but also his sponsor in North Carolina no longer needed him. Regardless of this information, the local authorities in New York City, no doubt overwhelmed with an inux of displaced persons from war-torn Europe, still put him rst on a train to Washington, then one onto Greensboro, North Carolina. I said, “my parents are on Long Island, why I do I have to go there?” The guy said, “That’s where you have to go.” In 194818In 1947

Stefan was in North Carolina for a week and met a local priest that helped Stefan get back to his family in New York. The Kańdułas, including his younger brother Frank and sister Mary, were by now working on a farm in Long Island owned by a man named Tony Tyska. An enterprising businessman, Mr. Tyska ended up sponsoring Stefan to come over and work on the farm as well.You had to be as healthy as a bull to be accepted by a sponsor. In 1950, Stefan and his family had comfortably settled into their new home on the Tyska farm. We grew cabbages, tomatoes, cauliower, cucumbers, and potatoes. Tony bought livestock. My father would milk the cow and take some milk for his kids, and he was given meat from slaughtered pigs. Around the same time, Stefan’s got word from his former sweetheart and future wife, Jadwiga Szemiot, aged nineteen, that she had arrived in America.She was sponsored in Texas. She worked as a maid and was paid a dollar a day to watch three boys and clean house. 19Stefan’s mother, Apolonia, as a member of a Women’s Auxiliary Association, Long Island, NY, 1953

Deeply unhappy in Texas, Jadwiga desperately looked for a way to relocate as soon as possible. Her friends told her that there were jobs everywhere in Chicago and she pounced on the idea. Shortly after she moved to Chicago, Jadwiga’s mother died suddenly of a brain aneurysm in December of 1950. Stefan notes that Jadwiga was left alone to care for her family and would be haunted by this tragedy for the rest of her life. Jadwiga came to visit me and gave me an ultimatum: if you don’t come to Chicago within a week, forget it. So I agreed to go to Chicago. In May of 1951, Stefan left for Chicago, after only a little over a year of living in Long Island with his family. He moved in with Jadwiga and her father and brother at 1955 West Evergreen in the Wicker Park neighborhood on the west side of the city. They were married a few months later in a civil service on July 7, 1951.The landlady put up a ght because she said we were living in sin. So, we were married in a civil ceremony. We didn’t know how to get to city hall, so my wife’s brother took us there. We needed a witness, so we asked the couple who were getting married before us. We were their witnesses and they were witnesses for us. 20Stefan and Jadwiga, wedding day, 1951

Until her death in 2016, Stefan and Jadwiga were married for sixty-ve long years. Although their marriage was tumultuous at times, Stefan honored the vows he made to his feisty, young bride so many years earlier. He shared that while he had some reservations about getting married at the time, he went ahead with it anyway because he is a man of his word.One thing led to another and we got married. I was twenty-three and my wife was twenty. We made a stupid promise to each other back in Germany. When I make a promise, I keep it. If you can’t keep a promise you are good for nothing.On October 14, 1951, Stefan and Jadwiga were married in a church ceremony. This would be the anniversary date they’d celebrate with friends and family for the next sixty-four years. We found the apartment on Evergreen via a newspaper ad. Helen and Frank Maniak were the landlords. They were sympathetic to us because they were Polish immigrants, too. Someone told me, “Keep the money in your hand when you talk to the landlady so she knows you can pay.”Space was cramped in the apartment, as Stefan, Jadwiga, her father, and Jadwiga’s little brother Jozef all lived in a space they shared with another family. Rentals were hard to come by in Chicago. Garages were converted into actual dwellings because there were so many immigrants coming to the city.21Stefan’s parents, Apolonia and Frank, 1951

We lived a seven-room apartment divided into two units. We had two small bedrooms and a kitchen, and a shared bathroom.Soon after settling into their new home, Stefan landed a job at Salisbury, a rubber factory located at 401 North Morgan Street in the West Loop. I was a pressman—cooking and pressing rubber into huge sheets to make insulation wrap for electric wiring. It was a night job, and I earned $1.05 an hour. I worked there for twenty-one years. Another big change would take place in the Kańduła-Szemiot household in August of 1952 when Stefan and Jadwiga welcomed their rst child, Krystyna, into the world. Then, ve years later, their rst and only son, Jerzy (known to the family as Jurek) was born on January 3, 1957.Our neighbors didn’t appreciate the crying baby, and they eventually moved out. So, we took the other half of the apartment.Later that same year, Stefan, Jadwiga, Krystyna and Jurek moved to a house on 3406 West LeMoyne in the Chicago neighborhood of Humboldt Park to accommodate their growing family. They remained there for next nineteen years.22With Krystyna, 1955

We had lots of Polish neighbors. I remember taking the kids to Humboldt Park to play.A few years after they settled into their new home, they would welcome another daughter, Irena on August 22, 1960. Their family was complete nally, when on January 1, 1968 their youngest daughter, Teresa was born.All these kids made me think that I would have to work more to provide for the family. All I thought about was work.In 1968, Stefan landed a job as a precision grinder with American Spring and Wire. I earned $1.60 an hour. Occasionally, you’d get a ve-cent raise, but you also got time-and-a-half if you worked overtime.The more Stefan produced, the more money he made. Work was work. I got a check every week, and that was it. It paid the bills. Staring at the grinder all day, you’d get dizzy. Some people were into making more and more money. Stefan had a more realistic outlook. If I can make it, I make it. Nothing more. 23With Irena, 1960

When not working, Stefan dedicated his free time to spending time with his family and has many fond memories of being with the kids.I remember taking them grocery shopping and teaching them how to drive. I taught Michelle, my granddaughter, too.Other treasured memories include trips to Long Island to visit Stefan’s family. His sister Mary, who had three children, and brother Frank, with his four kids, along with all the cousins, enjoyed playing together on the beach of the Atlantic Ocean. Today, Long Island is a lot dierent than it was in the old days. All the people who live out there now are celebrities and then there are the people who work for them. We are the people who work for the celebrities.Back home, Stefan worked many night shifts at American Spring to support the family. But the neighborhood climate in Humboldt Park was shifting in the 1970s, and it was becoming more dangerous. One night, he was mugged outside his garage. Krystyna, Stefan, Irena, and Jerzy, 1961

I was hit with a gun on the head. Blood was everywhere. I needed more than a dozen stitches. That was enough to move the family out of Humboldt Park. In 1976, the Kańdułas bought a house at 3627 N. Linder in the Portage Park neighborhood. The blond brick bungalow, which he still owns today, holds many good memories. Wiligia (the traditional Polish Christmas celebration held on December 24th begins with a meatless meal served in the early evening), birthdays, anniversaries, graduations, Mothers’ and Fathers’ Days were all celebrated here often accompanied by home-cooked meals.We celebrated holidays and birthdays in the Polish way, with plenty of potatoes, herring, mushroom soup, macaroni and cheese, and biscuits. This house was always full of people.As the years passed, Stefan’s children grew up, moved out and began families of their own. Life began to slow down. Suddenly, in June of 1991, after complaining of severe headaches for several weeks, Jadwiga suered an aneurysm when a blood vessel in her brain gave way to the mounting pressure and burst. 25In 1974With family, 1967

The doctor operated for six hours. He said, “One more minute, and she would have been gone.” Doctor said she would live six to seven years. She lived twenty-ve more years, but she had dementia. Miraculously, despite the grim odds of survival, Jadwiga recovered. Her ery spirit kept her going and kept Stefan on his toes for another quarter century. Finally, after battling growing dementia and a series of more frequent minor strokes, she passed away on July 7, 2016.We were married sixty-ve years to the day. Stefan candidly describes his marriage as hard and challenging, and there were times that he was tempted to leave. There were big ghts. She was always jealous of other women. Even just me saying, “thank you, have a good day” to another woman made her angry. Something kept me from leaving. I’m glad I didn’t. Although there have been other tragedies, such as the sudden death of his oldest daughter Krystyna in May of 1995 from a massive heart attack following a long battle with chronic Multiple Sclerosis, it is his family that is Stefan’s anchor during the roughest times in his life.26Celebrating their 25th wedding anniversary, 1976

After the death of his wife, Stefan moved in with his daughter, Irena. The process of cleaning out the house on Linder to prepare it for sale has been slow (at print, his children have been dedicating three-to-ve hours nearly every Saturday for over two and a half years on the project). Each week, memories are resurrected with the discovery of some family heirloom or token. One of Stefan’s old wallets from the early 1990s, stored in a drawer in a spare bedroom, contained photos of every single one of his family members from his parents down to his youngest grandkids. You could tell he was proud to oer friends and acquaintances a “ip-book” tour of the people who meant everything to him. It’s delightful to see him interact with his younger brother. The two have committed to a weekly phone call each and every Sunday. When asked what family members thought of Stefan, this is what some of them shared about him:• Frank (brother): If you ask him for help, he helps you out and vice versa—he’d come here [Long Island] if I needed him and I’d go to him if he needed me.”27Stefan (right) with siblings Frank and Mary in South Hampton, 1980s

• Irena (daughter): He was our safety net. If it weren’t for him, we’d probably be in jail. He was our protector and buer from my mother. • Jurek (son): He is as good a dad as you can get. • Teresa (daughter): Whenever my Dad had a task, he would always whistle or hum a tune while he worked. It was as if it helped him focus and I remember he was always busy doing something because something always had to be done (even if it was just to get away from my mother). I learned a lot from my Dad especially hard work, patience and perseverance. Thank you, Dad.• Anna (granddaughter): “When my parents died and I inherited our home, I found myself overwhelmed by the repairs it needed and I actually prayed for someone to help me. One day when I got home from work, I found my grandfather working on xing a few steps and reinforcing the foundation of my porch and I laughed out loud. He wasn’t exactly what I had in mind, but he was denitely the answer to my prayers!• Michelle, “Shelly” (granddaughter) “The things I love about Dziadzia are his drive, his loyalty and his heart. He followed a woman and married her. He stayed by her through thick and thin, sickness of all sorts and still loved her.”With family, 198728

• Adam (grandson)“It’s not often enough that I express my gratitude towards him. He’s constantly served as a voice of calm reason—weathering the storms of life with poise. However, he never forgot to bring lighthearted tomfoolery to the table, as life cannot be lived well without mirth. A sort of having your cake of responsibility and duty while also managing to eat it for breakfast.”• Daniel (grandson) “He is a source of inspiration to me of what can be accomplished in life so long as you try and give it your best eort. Dziadzia always made sure to tell me (and I am sure anyone in our family) to, ‘Do a good job.’ Whether it be school, work, a relationship, or frying a pierogi.”• Nicolas (grandson) “The values my Dziadzia instilled in his family are still present in all of us today. From being level-headed and light-hearted in the most troubling of times, to being hard-working and perseverant. I’m proud to have inherited these values.”• Michael (grandson) “Dziadzia always has a big hug and a big smile for me every time I see him. He always makes me happy whether it is coming to my games to watch me play or just making sure I’m doing well. He inspires me to keep working hard.”29With daughter Teresa on her wedding day, 1992

• Faith (great-granddaughter) “I loved when he gave me the military money, a Russian bill, and told me stories of how things were for him growing up.• Cecilia, “Ceci” (great-granddaughter) “I love when he would sit on the porch and talk to us.”• Noelle (great-granddaughter), “I loved when he came to our church, outside of the church, and used his cane to hit the ‘broken bell’. He kept telling me to hit it, too.”Stefan has been blessed with six grandchildren: Anna (b. 1978), Michelle (b. 1978), Adam (b. 1988), Daniel (b. 1991), Nicolas (b. 1996), and Michael (b. 1999). I’m very proud of my grandkids. I feel very loved. He is also now a great-grandfather to Faith (b. 2008), Cecilia (b. 2009), Noelle (b. 2011), Tyler (b. 2014), and Mallory (b. 2016), who all love to be around their “Pra-Dziadzia.” 30Posing with visiting South Hampton family, 2010

They make me feel that I did something good. Stefan makes a point to make sure they know his name. Stefan: What is your name? Great-Granddaughter: Noelle. Stefan: I’m Stefan. I have a name like your father. I have a name, too!And now they know his story, too. Stefan lives a life of perseverance: living through World War II, becoming a refugee, building a new life in America, raising a family, and holding his marriage together. Everything was a challenge and nothing came easy. Whatever I had, I had to earn myself. But looking back, Stefan is full of gratitude for his family.I have no complaints. I’m happy how I raised the kids--everyone turned out okay. I made a life for my children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. After all his work, Stefan oers the following parting advice to his descendants: You’re here because of me, so don’t screw it up!31Pra-Dziadzia to (l-r) Ceci, Noelle, Mallory, Faith, and Tyler, 2016

32

33

34